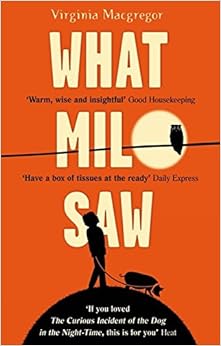

Title: What Milo Saw

Author: Virginia Macgregor

Published: 13th August 2015

Publisher: Sphere

Today's post is my stop on the Blog Tour for What Milo Saw by Virginia Macgregor with a wonderful original post from Virginia on where she writes and an Extract of the book to share with you. The other stops on the tour are listed below, so don't forget to stop by their blogs for some other great posts.

Where I Write by Virginia Macgregor

Is there a special place that inspires you, what is your writing room/office etc. like?

We are all, to some extent, the product of our mother’s habits. As a post-war child, chased out of Berlin by the Russians, my mother developed a nomadic soul and has spent the last 73 years living out of suitcases. This gave her a framework for thinking and living. All your activities should be portable was her refrain when I was little. You must learn to carry your life on your back, like a tortoise. A tennis racket slung across one shoulder, a violin across the other. A head filled with a thousand songs. Paperbacks (or as the French would have it livres de poche) tucked into your jeans. Being a writer fitted perfectly into this scheme. A pen. A notebook. A metaphorical rather than a physical desk. Confidence in the knowledge that all I need is words, a keen sense of observation and a bit of imagination.

I love my beautiful white wood desk with its blue inlay, nestled in the back room of my home in Shinfield, a desk given to me by the parents and pupils from my time as a housemistress. I love the books that surround me. The collages of my latest writing projects. The encouraging notes from my husband, Hugh. The window that looks out onto trees and birds and the patch of green that is our back garden.

But I also love the knowledge that I can write anywhere – and I often test this. I write in bed. In libraries. In coffee shops (how I love coffee shops), in hospital waiting rooms. On trains and buses and planes. Perched on park benches. Leaning up against thick tree trunks. In cars. At people’s kitchens tables. And because writing is an ongoing process, as much about thinking as actual scribbling, I write in places less amenable to pen and paper too – in the bath, on the loo, whilst walking. And I train myself to deal with disruptions. Music in coffee shops – and the grind of beans and the hiss of steam and the shouts of baristas. People speaking on their mobiles. Sirens. The jingles of ice-cream vans. My cat, Viola, padding across my keyboard. And soon, the cries and wriggles and demands of a newborn baby. It is my ambition to write anywhere and at any time and in any circumstance. To take my mother’s advice to its limit. Because then there’s no excuse, is there? I just have to keep writing.

Milo sat at the computer on the landing listening to the shush-shushing of the firemen’s hose on the drive. The firemen had only just let them back into the house.

‘I want a list of nursing homes,’ said Mum.

‘Can’t Gran stay till Christmas?’

Gran was Dad’s gran and Milo’s great-gran but everyone just called her Gran.

Milo turned his head to look at the fairy lights he’d wound round the banisters leading up to Gran’s room. He’d had the idea when he saw her struggling to find the light switch. Mum guided Milo’s head back to look at her and said ‘No.’

‘But . . . ’

‘Don’t insist,’ said Mum and then pinched shut her mouth.

Don’t insist was Mum’s favourite phrase of all time.

‘But Mum – the fire was my fault, I should have gone down to check.’And it was true. Every morning when Gran padded down the stairs from her room under the roof all the way to the kitchen and made her cup of sweet, milky tea, it was Milo’s job to make sure she was okay. He’d lie in bed and listen for the clues:

1. The clink of Gran’s tartan mug as she pulled it off the mug tree.

2. The suck and pop of the jar with the tea bags.

3. The rattle of the cutlery drawer as she took out her favourite teaspoon, the one made of real silver with a kink in its handle.

4. The kettle filling up (though usually Milo tried to remember to fill it up the night before because Gran’s wrists were weak and she struggled to hold the weight of so much water).

5. The click of the switch on the kettle.

6. A pause.

7. And then the water heating, steam pushing at the lid, bubbles rolling over each other like a hot sea, and then another click when it was done.

8. Sometimes, after step 3, Gran forgot they had a kettle and she’d open the saucepan drawer and fill a pan up and light the stove. That was the cue for Milo to swing his legs out of bed and come downstairs.

They had a gas hob and Gran wasn’t allowed to use it. Milo didn’t know why he missed the sound of the saucepan drawer that day. He must have been sleepy or maybe Gran was extra quiet, but by the time he felt the flutter in his chest which told him that Gran needed him, and by the time Hamlet was squealing his head off in the garage because he’d swallowed too much smoke, it was too late, the kitchen was on fire.

‘It’s not your responsibility to check on your gran,’ said Mum.

She leant in and kissed Milo’s hair. She was always doing that: telling him off and then kissing him. She smelt of burnt things and sticky perfume and sleep.

‘When all this is over, I’ll let Hamlet stay in the house,’ she said.

Milo leant under the desk and gave Hamlet a rub between his ears. The only reason he was allowed up here now was because the fire had scared him. Milo hated the fact that Hamlet had to live in the garage all by himself: the garage was cold and damp and didn’t have any windows. No one should live like that. But if Milo had to choose between Hamlet coming out of the garage or Gran getting to stay with them, he’d have to pick Gran. Hamlet would understand. Mum looked over Milo’s shoulder at the computer screen.

‘We don’t want anywhere fancy, Milo, Gran wouldn’t like that.’

So Milo tried typing not fancy nursing homes into Google but Google didn’t get it and wrote back: did you mean fancy nursing homes?

Once Milo had stationed Gran safely on the drive and once he’d yanked open the main door to the garage and got Hamlet out of his cage and given him to Gran to look after, he’d come back inside and screamed: Fire! Fire! Mum! There’s a fire!

Mum had come tearing down the stairs and out of the house, her non-make-up face all pale and puffy. When she saw Gran she didn’t ask how she was and she didn’t say she was relieved that Hamlet was safely out of the garage and she didn’t tell Milo well done for having saved everyone. She just yelled the same words over and over:

This is the last straw. This is the last bloody straw.

Milo and Gran both knew what the last bloody straw meant: it meant that Gran was going to a nursing home.

Mum jabbed a chipped pink nail at the computer screen.

‘Those rooms are far too big,’ she said. ‘Gran will feel lost.’

So Milo did a search for nursing homes with small rooms. But then he thought about all the stuff Gran had upstairs, like Great-Gramps’s bagpipes and his uniform and the boxes of letters he’d written her and her map of Inverary and the picture of her fishing boat and her small radio and how she’d want to take it all with her.

‘It’s not coming up with anything.’ If Milo made Mum feel it was a hassle, maybe she’d back down.

‘Oh, for goodness sake, Milo.’ Mum looked up the stairs to Gran’s room and scratched a red bit on her throat. Then she leant in and whispered, ‘Just find somewhere cheap.’

Mum wrote the word CHEAP on the back of an envelope and placed it right in front of Milo so it wasn’t lost in the fuzzy bit of his vision. He ran his fingers over the word; she’d pressed so hard on the pencil that the letters felt bumpy.

‘I’ve got to make the firemen some tea.’

Still in her nightie (the frilly one that looked like the kitchen curtains, or how they looked before they caught fire and turned into black moths on the linoleum floor), Mum rushed back downstairs. Milo heard the cupboard door open and the rustle of the Hobnobs packet. The plastic kettle had melted, so Milo didn’t know how Mum was going to boil water for the tea.

Milo wasn’t going to let Mum stick Gran in a nursing home. He’d pretend to go along with it and then Mum would calm down and realise that Gran belonged right here in the small room Dad had converted for her under the roof, and that Milo was the best person to look after her. Then they’d have a proper Christmas, the four of them: Milo, Gran, Hamlet and Mum. Milo scanned down the list of homes on the screen. They all had garden centre names like Acorn Cottage and Birdgrove and Beechcroft Hill and Bird Poo View. He madeup the last one. Milo typed: not cheap nursing homes into Google and waited for a new page to load.

‘Found anything yet?’ Mum called up the stairs.

The burnt smell had crept into the carpet and curtains and walls and was making the back of Milo’s throat tickle. He coughed and called back: ‘Nearly!’

‘Well, when you have, give me the phone numbers and I’ll organise some visits.’

Milo didn’t answer. Above him, the floorboards creaked and then water juddered through the pipes. He hoped Gran would remember to turn off the tap. As soon as he’d finished making this stupid list, he’d go up and tell Gran that there was no way he was going to let Mum kick her out. He’d work out a plan that guaranteed she could stay, and not just for Christmas.

No comments:

Post a Comment